The Oude Lijn (Old Line) is the original railway line that runs from Amsterdam Centraal in North Holland (Amsterdam’s central train station in its city center) to Rotterdam Centraal in South Holland. It was constructed on a centuries-old path of commerce. The longtime method of passenger travel between cities on this old Dutch trade route had previously been the trekschuit (horse-drawn boat), a small canoe that was pulled through various canals and other waterways by a horse walking on land. The idea of the Oude Lijn was politically controversial because it threatened long-established marketplaces on the numerous rivers and canals that had been trade settlements for centuries.

The first leg of the rail line from Amsterdam to Haarlem was completed in 1839. Its track gauge (the distance between the two rails on the track) was 1945mm, which was broad for the time. Several decades later, it was narrowed to a 1435mm gauge, also called the Stephenson gauge, to standardize the Dutch rail network with the German model. The first trains were steam locomotives that traveled the 19km from Amsterdam to Haarlem in a then-record 30 minutes. Construction on the Oude Lijn was expanded to the Hague by 1843, and by 1847, it had reached Rotterdam’s Delftse Poort station at its city center (just east of what is now Rotterdam Centraal). A major railway station was completed as part of the project, thus connecting the track to Amsterdam’s Willemspoort station to officially form the Oude Lijn.

The Oude Lijn’s subsequent rise in the 19th century established Rotterdam as an economy based on supply chain and logistics. Although it was positioning itself as the regional supply chain hub in trade from the UK to Germany, it was not yet a renowned global port city. Advances in technology-enabled merchant vessels to be built larger with more cargo space, but those that were too large would run aground in the shallow water. As such, a massive hydraulic civil engineering endeavor was commissioned by the Dutch government in 1863 with the goal of allowing access to Rotterdam through the North Sea for large, modern seafaring vessels by cutting through an area called the Hook of Holland. The dredging and excavation, which dug through wide dunes at great cost, ultimately created the Nieuwe Waterweg (New Waterway) in 1872, giving rise to an artificial mouth of the River Rhine which was then able to accommodate large barges (30 meters long and 10 meters wide in that era) and ocean-going ships via shipping lanes that had not previously been able to access Rotterdam through the narrow canals and waterways. The Nieuwe Waterweg is still fully functional today as a passageway for supertankers and the world’s largest cargo ships.

Its deep-water access immediately brought prosperity to Rotterdam. By 1961, it was the #1 cargo port (in annual cargo tonnage) in the world, surpassing the port of New York. It remained #1 until 2004, establishing Rotterdam as a supply chain epicenter. Rotterdam has been the largest port in Europe since the 1950s and remains so. In 2022, it welcomed the Ever Ace (the world’s largest container vessel) on its maiden voyage to the Port of Rotterdam, where it transported 24,000 TEUs to its Delta Terminal to unload cargo.

The expansion of the Port of Rotterdam, combined with the Oude Lijn and increased use of rail in Europe, firmly established Rotterdam as a global port city. The Oude Lijn ran on electricity between 1924 and 1927 but was destroyed in the Rotterdam Blitz in 1940. It has grown to the point where a total of 31 stations are currently functioning on the line today to accommodate the passenger and cargo stops necessary within its boundaries.

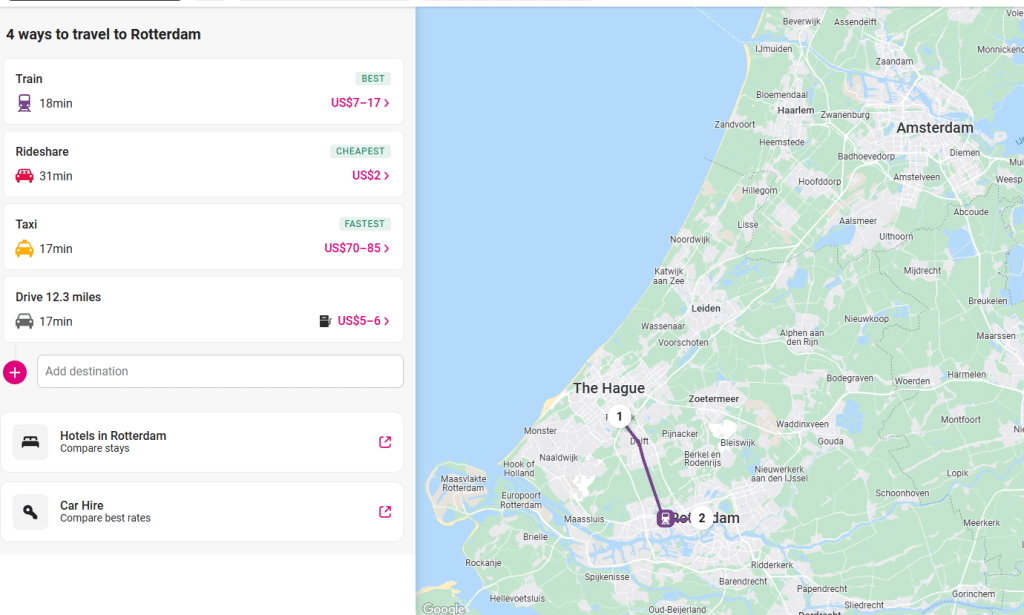

Although Amsterdam and Rotterdam are only 58km apart (Amsterdam has over 200K more citizens although Rotterdam is larger in size by 100km) they have the two largest economies in the Netherlands. The tourist- and management-based economy in Amsterdam and the supply chain-based economy in Rotterdam are different but complement each other, as Amsterdam’s Schiphol airport is Europe’s fourth-largest and the Port of Rotterdam is Europe’s largest.

The two cities’ architectural styles outside their main train stations are completely different: Rotterdam’s city center is modern and global due to the rebuilding that took place after the Rotterdam Blitz, whereas Amsterdam’s city center is known for its Dutch Baroque style. Tens of thousands of employees in Rotterdam commute from Amsterdam on the Oude Lijn, some of the more than 60% of Dutch citizens who commute to work.

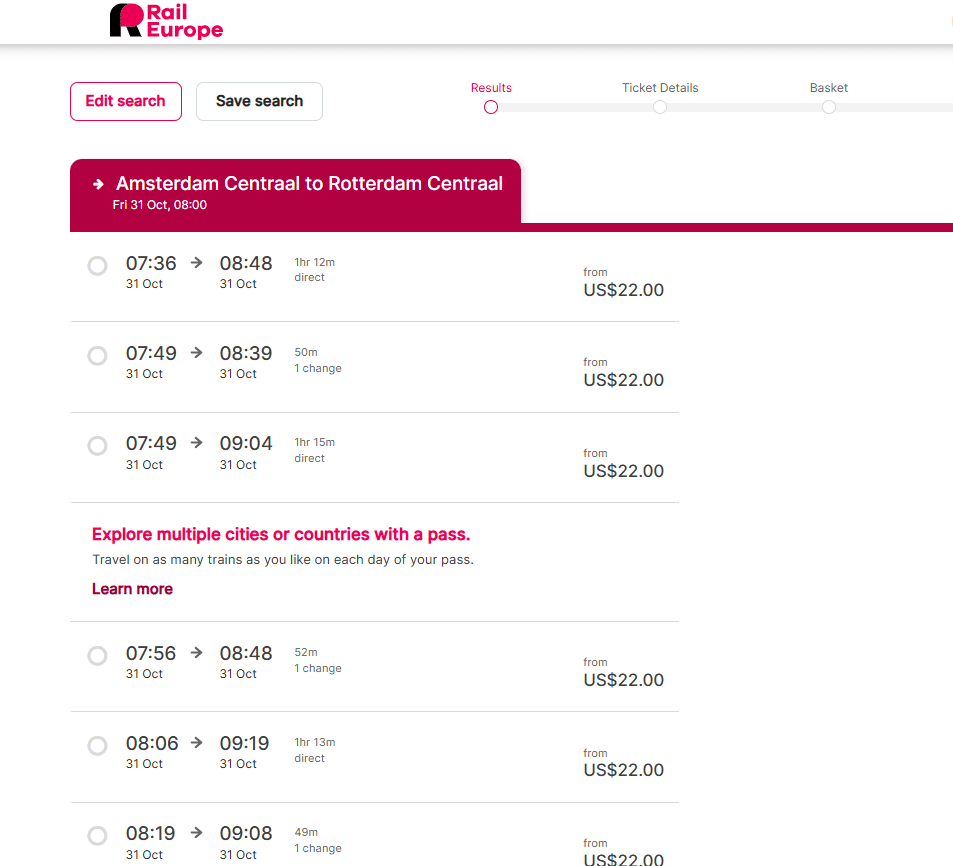

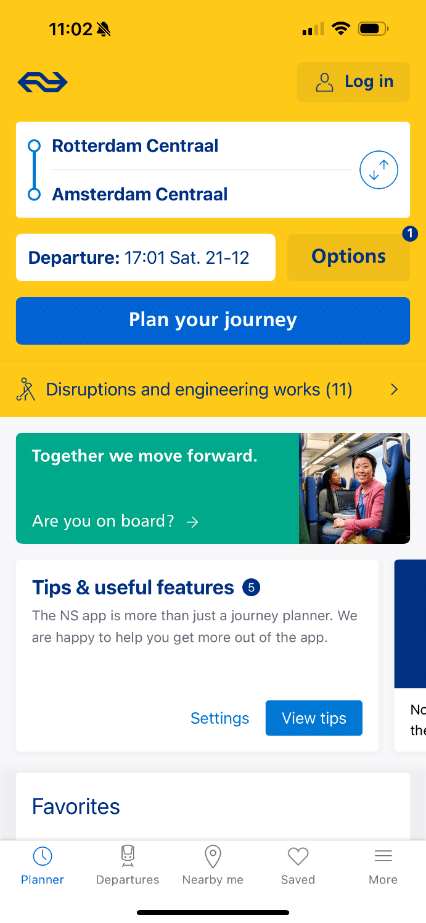

The state-owned Nederlandse Spoorwegen/NS (Dutch Railway system) offers two different types of passenger trains between the cities: Sprinters and Intercities. The NS, Rail Europe, and EuroCity are popular among other vendors that offer round-trip Oude Lijn transportation on the Intercity Direct (high-speed train) service for about €24. The Intercity Direct train is a faster version of high-speed rail that uses the Oude Lijn’s HSL-Zuid/Ogesnelheidslijn Zuid (High-Speed Line South) at a cost of about €3 more than the Sprinter, a train for short distances which stops at smaller stations. About 80-100 Intercity Direct trains run at regular intervals per day, offering longer-distance travel and stopping at fewer stations. This compares to the 200 Sprinters running between the two cities, which take 63 minutes of travel time and arrive every 15-20 minutes.

Modernizations and innovations are continuously prioritized. Upgrades on the Oude Lijn are spearheaded by the High-Frequency Rail Transport Program, a Dutch infrastructure project managed by ProRail, the central authority of the Dutch government’s national railway network (under the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management), which serves as an intermediary to facilitate with rail carriers and contractors, to facilitate enhanced travel between regions.

A particular focus of this program is the busy Rijswijk-Rotterdam (Hague-Rotterdam) corridor of the Oude Lijn in west-central Holland, which has a goal of running eight Intercity trains and six Sprinter trains per hour in each direction between Den Haag Centraal (The Hague’s central train station) and Rotterdam Centraal. This section is also the center point of an innovative up-and-coming light-rail network that links the area by metro system/public transportation. This efficient transit system’s infrastructure often utilizes trams whose power is drawn from an overhead electric line on dedicated and/or shared tracks (to complement the traditional underground metro systems), which is more common to the various city centers in the corridor, with the goal of enhancing passenger movement and efficiency.

The light-rail Rijswijk-Rotterdam corridor is a lynchpin in the broader development of these regional economies. Current plans for the Rijswijk-Rotterdam corridor include new underpasses and modernizing of stations. For instance, the Delft Campus Station in the college town of Delft on the southern section now offers the first energy-neutral Dutch train station, with 810 solar panels on the roof generating 200 megawatts of electricity per year and the number of tracks being expanded from two to four. Due to their geographic proximity, 106 trains travel between Rotterdam and the Hague per day, taking just 26 minutes, but further development is anticipated.

Typical Rotterdam public transport passes allow for free movement to the Hague, although it takes a bit more time than the high-speed Intercity Direct option. Metro Line E (the dark blue line) makes the trip in 26 minutes with stops at 13 stations. Kiosks at the stations offer tickets for 1-, 2-, or 3-day traveling. Most tourists use disposable OV-chip parts (OV-chipcards) for public transport while in Rotterdam; these are available online and at the airport as well as at Rotterdam metro station kiosks for €7.50/day. Visitors are encouraged to use public transport to get around, including light-rail trams, buses, trains, and/or metro systems. While tourists generally buy disposable (cardboard-copy) cards, residents usally utilize personal OV-chipcards with their name and passport photo, equipped for routine credit card pay, in a wallet or purse.

While in Rotterdam, public transport apps have become commonplace so travelers can easily determine the most efficient methods to get from place to place. The Rotterdam Electric Tram Company (RET) manages the schedule and residents generally use the RET app, which shows real-time information related to metro, tram, and bus arrivals and departures. The 9292 and DVP apps are also useful for Rotterdam public transport. The NS provides real-time train schedules and fares at €15.50 for a day ticket for tourists via RET. With air quality and energy efficiency in mind, the RET network introduced 55 fully electric buses in 2019 with the goal of a completely emission-free bus system by 2030.

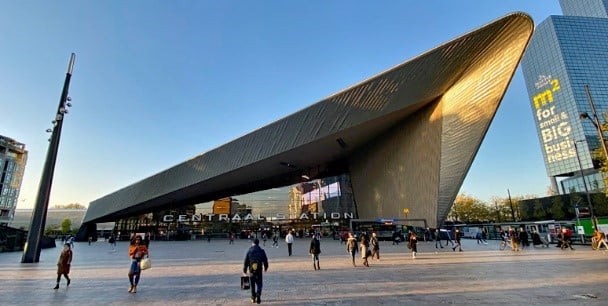

The Oude Lijn and its light-rail corridor from Rotterdam to the Hague are regional Dutch versions of what the continent at large envisions as the way to connect locations as economic integration and free trade continue to permeate the political and economic landscape. Rotterdam Centraal is the centre point. Completed in 2014, it is a multi-mode transportation hub constructed on an open public square and geographically centralized in the city. It has a modern stainless-steel exterior and serves more than one hundred thousand travelers every day. Outside is Stationsplein, the city’s urban mobility hub, which was initially a transportation center but has grown into a public space in the middle of Rotterdam Central District, the busy business district where modern architecture meets modern infrastructure such as the red Dutch bike lanes.

An expansion of the light-rail network is being strategized because it could connect Rotterdam to geographically proximate areas not far away. For instance, Paris is considered a prime future outpost at merely 450 km away. Currently, a high-speed train from Rotterdam to Paris takes less than 3 hours for a cost of €38. It is accessible via Eurostar, a Western European high-speed rail service, but not via light rail. Rotterdam’s light-rail system could also connect Antwerp, Belgium (the second largest port in Europe, 79 km away), The Hague (20km away), Utrecht (48 km away), and several German cities including Dusseldorf (224 km away). Many envision a late 21st-century European rail transport network that can quickly move people and cargo and serve as a model that population clusters around the world could follow. For example, China is currently planning similar infrastructure planning endeavors.

The Rijswijk-Rotterdam corridor within the Oude Lijn is an integral part of the emerging Rhine-Alpine corridor, stretching from the North Sea ports of Rotterdam south through the continent to the Mediterranean basin in Genoa, Italy. Much still needs to be constructed, but the goal is for this track to stretch through five countries. It is considered a possible destination for future heavy freight and light-rail opportunities, reflecting a continent-wide mindset of shifting movement from road to rail.

From its trekschuit past to the current innovations and aspirations in light-rail, the Oude Lijn’s continued impact and its role in building up Rotterdam into a supply chain epicentre is undeniable. The city of Rotterdam and other transportation stakeholders will continue to plan and innovate in the future.

Author – James Tanoos, Clinical Associate Professor, Purdue University, Indiana, USA

References:

https://int.anteagroup.com/projects/high-frequency-rail-transport-program-in-the-netherlands#91402